July 19, 2005

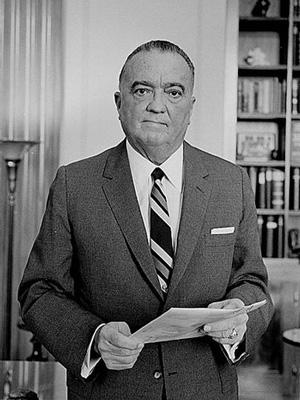

J. Edgar Hoover in 1961

The Truth about J. Edgar

Hoover

by Mel

Ayton

Since the

death of J. Edgar Hoover in May 1972 stories about him have continued to

fascinate the American public. Initially characterized as a true

American hero who spent a lifetime battling crime, his legacy during the

past decade has undergone a startling transformation. Recent books,

television documentaries, and television movies have promoted the idea

that America's leading crime fighter was steeped in corruption, trampled

over the constitutional rights of American citizens, blackmailed members

of Congress, engaged in illegal electronic surveillance activities, was

himself blackmailed by the Mafia, and engaged in perverted sexual

activities.

But what is the truth about America's

greatest crime-fighter? Did Hoover associate with Mafia bosses and

perhaps assist them in avoiding prosecution? Did mobsters blackmail him?

Did he, in turn, blackmail U.S. politicians? Did he, in particular,

blackmail JFK? And was Hoover a closet homosexual and

cross-dresser?

Hoover's Rise

The FBI's origins lie in the crime-ridden

Roaring Twenties when the United States was rife with lawbreakers. It

was against the law to make or consume alcohol and yet millions of

Americans refused to recognize this fact. The distillation and

distribution of alcohol became big business involving millions of

dollars and corruption of public officials on a scale unheard of either

before or since.

Criminal gangs competed for the business

of supplying the public what it wanted. Violence was inevitable as

gangsters moved into territories owned by competing gangs. The violence

and corruption was significant in the growth of the American

Mafia.

The United States had no national police

force at this time, but Congress decided that a federal force was

necessary to deal with a law-breaking situation that was becoming too

big for state and city police forces. Congress chose a small department

within the Justice Department headed by an unknown professional

bureaucrat by the name of J. Edgar Hoover.

When Hoover took over the newly formed

Federal Bureau of Investigation its resources were limited and Congress

had not yet passed laws to strengthen the authority of its agents. Under

the leadership and persuasive skills of Hoover, the department expanded

to become a world-famous and internationally acclaimed institution.

Hoover's "G-men" became national heroes as they captured notorious

criminals such as John Dillinger, Ma Barker, Machine-Gun Kelly and

leading members of criminal gangs. The titles "Public Enemy No. 1" and

"The Ten Most-Wanted" list originated with the bureau. Hoover became a

national hero, in part because of his publicity skills and his ability

to persuade politicians and presidents to expand the authority of the

FBI. Hoover did everything in his lobbying and blackmailing powers to

see that Congress was generous with the bureau's budget. Hoover also

strictly monitored anything that extolled the virtues of the FBI, from

books, television and radio serials, to Hollywood movies.

Hoover was partly successful because he

changed crime fighting into a science. He instituted fingerprint files

and laboratories to analyze forensic evidence, stipulated that FBI

applicants had to have a college degree and insisted his agents had to

practice a high personal moral code. During the Second World War, the

bureau successfully fought efforts at sabotage and subversion by the

Germans and they could proudly point to the fact that not one instance

of sabotage on the U.S. mainland was successful. After the war the FBI

was also successful in detecting and arresting many Soviet spies. Hoover

was convinced there was an international left-wing conspiracy to take

over the world and, during the late 1940s and 1950s, most of his

energies were devoted to rooting out anything that smacked of communism

or socialism.

Recent research has suggested that the

idea of subversion by the Soviets was not all in the imagination of

right-wing politicians or the conservative FBI director. There is a

wealth of evidence to confirm that the Soviets were actually using every

means available to infiltrate the U.S. government and any other

institution in the United States that had political and cultural

influence. Hollywood was a particular target for communist cells.

However, many lives were destroyed because of the paranoiac hysteria

that often accompanied right-wing Congressional efforts to "clean up"

the movie industry.

Hoover and the Mafia

It has been alleged that, during this

period of anti-Communist fervor, Hoover had been blind to the existence

of a national crime syndicate even though a 1950s Congressional

investigating body led by Sen. Estes Kefauver had produced a mountain of

evidence proving this fact.

After the nationally televised Kefauver

hearings, Hoover still insisted that there was no such thing as the

Mafia and as a consequence there was a period of consolidation of the

criminal organisation and a period of growth for Mafia "families" in

every major city across the United States.

Some critics argue this was entirely in

keeping with Hoover's basic conservative philosophy that respected the

importance of states' rights.

Similarly, when there was a move in

Congress to make him the head of a nationalized police force, he

rejected the idea and testified against it. In an interview with U.S.

News & World Report (December 21, 1964), he argued, "I recently

made the statement that I am inclined toward being a states' righter in

matters involving law enforcement. That is, I fully respect the

sovereignty of state and local authorities. I consider the local police

officer to be our first line of defense against crime, and I am opposed

to a national police force...The need is for effective local action, and

this should begin with whole-hearted support of honest, efficient, local

law enforcement."

Anthony Summers, in his book Official

and Confidential, claimed Hoover deliberately refused to crack

down on organized crime because he was being blackmailed by the Mafia

for living a secret life as a homosexual. Summers believes that Hoover

was blackmailed after powerful Mafia boss Meyer Lansky, an associate of

Frank Costello, obtained photographs of the FBI boss in a compromising

position with his friend and top aide, Clyde Tolson. Summers's "proof"

about Hoover's homosexuality comes from a number of witnesses who told

him that they had seen such photographs. Former members of the Mafia or

Mafia associates told of how Lansky pressured the FBI director into

leaving the criminal organization alone.

That Hoover was a homosexual did not

originate with Anthony Summers, however. Beginning in the 1920s, a

number of Hoover's agents speculated about their boss's sexual

preferences. They noted how, from the 1920s up to the time of their

deaths in the 1970s, Hoover and his friend, Clyde Tolson, went

everywhere together.

Throughout his period in office Hoover

used the FBI to squelch rumors that he was homosexual. He was vigorous

in his approach because he believed the allegations impugned his good

name and integrity. FBI agents often intimidated his detractors. Hoover

ordered them to demand that the rumor mongers "put up or shut up." It is

clear that Hoover was confident no evidence existed of any

indiscretions.

Summers's strongest source for Hoover's

alleged homosexuality is Susan Rosenstiel, the fourth wife of Lewis

Solon Rosenstiel, a mobster and distilling mogul. She claims to have

witnessed Hoover in drag at two orgies at New York's Plaza Hotel in 1958

and 1959. Sen. Joseph McCarthy's former aide, Roy Cohn, a known

homosexual, was (allegedly) also present. Rosenstiel's story could not

be corroborated as all the participants present at the parties are now

deceased.

Hoover biographer Richard Hack has quoted

an interview given by Roy Cohn shortly before his death from AIDS. Cohn

said, "(Hoover) wouldn't do anything, certainly not in public, not in

private either. Hoover was always afraid that someone who he saw, where

he went, what he said, it would impact that all-important image of his.

He would never do anything that would compromise his position as head of

the FBI – ever. There was supposed to be some scandalous pictures of

Hoover and Tolson – there were no pictures. Believe me, I looked. There

were no pictures because there was no sexual relationship. Whatever they

did, they did separately, in different rooms, and even then, I'm sure

Hoover was fully dressed."

Anthony Summers's "evidence" of Hoover's

homosexuality lacks veracity according to two of Hoover's most acclaimed

and authoritative biographers. Richard Gid Powers and Athan Theoharis

both believe Summers's sources are not credible. Athan Theoharis said

that the popularization of Hoover's homosexuality was the result of

"shoddy journalism."

Powers also questioned the reliability of

many of Summers's witnesses quoted in the book. Powers said that Hoover

was such a hated figure that many people were prepared to believe the

worst about him and to "badmouth" him. Powers cites John Weitz, a former

wartime secret service officer, who, according to Summers, was at a

dinner party in the 1950s when the host showed him a picture and

identified Hoover having sex with another man. Weitz did not himself

recognize Hoover and he refused to identify the party host. Nor did

Summers ever see the photograph. Another "witness" to the existence of

the photograph was JFK conspiracy fantasist, Gordon Novel, who Summers

admitted was a "controversial" figure.

Athan Theoharis successfully

demonstrated, in his book J.

Edgar Hoover, Sex, and Crime, that Summers's claims were not

credible. Theoharis stated that no evidence exists that would prove

Hoover and Tolson were sexually involved. Theoharis also believes Tolson

was heterosexual, citing reports by a number of Tolson's associates.

Theoharis believes that the likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual

desire at all. Richard Hack, on the other hand, presented evidence in

his 2004 book Puppetmaster

– The Secret Life Of J. Edgar Hoover to prove Hoover had a

sexual relationship with Hollywood actress Dorothy Lamour and a possible

intimate relationship with Lela Rogers, mother of actress Ginger Rogers.

When asked about rumors of a Hoover/Tolson homosexual relationship Hack

answered, "Oh, I know it wasn't. I know he wasn't." Hack's view is that

the mere fact that Tolson and Hoover allowed themselves to constantly be

seen in public, meant they could not have been more than close

colleagues. Hack said, "It became clear to me as I went deeper into the

man's psyche that if they were indeed lovers, they never would have been

seen together."

Of Rosenstiel's claim that Hoover was

homosexual, Theoharis wrote, "Susan Rosenstiel…was not a disinterested

party. Although the target of her allegations was J. Edgar Hoover, she

managed as well to defame her second husband with whom she had been

involved in a bitterly contested divorce that lasted 10 years in the

courts. Her hatred of Lewis Rosenstiel had led her in 1970 to offer

damaging testimony about his alleged connections with organized crime

leaders before a New York State legislative committee on crime."

Furthermore, she was a convicted perjurer and received a prison

sentence.

Theoharis's research is supported by FBI

Assistant Director Cartha DeLoach who said Rosenstiel blamed Hoover for

supplying her husband with damaging information used in her divorce

trial. Furthermore, according to Deloach, she had been peddling the

Hoover "drag" story to Hoover's critics for years without success --

until Anthony Summers came along.

DeLoach and Theoharis are also supported

by writer Peter Maas who discovered a fatal flaw in Summers's rendition

of events with regard to the cross-dressing story at the Plaza Hotel.

Maas said that in the period following the alleged incident at the Plaza

Hotel Hoover assigned FBI agents to investigate Lansky who supposedly

had the photos of Hoover in a compromising position. When the FBI office

in Miami complained that an investigation would be hampered by lack of

manpower Hoover wrote back, "Lansky has been designated for 'crash'

investigation. The importance of this case cannot be overemphasized. The

Bureau expects this investigation to be vigorous and detailed." Maas

also wrote that when he asked Lansky's closest associate about the

photo, the old man replied, "Are you nuts?"

Therefore, according to Maas, this memo

severely undermines Summers's thesis that Hoover could not act against

mobsters because they "had the goods" on him.

And Susan Rosenstiel's credibility is

also undermined by her interview to a BBC documentary team. When

questioned by Anthony Summers about her observations at the Plaza Hotel

she said the person in drag "LOOKED LIKE J. EDGAR HOOVER." (Emphasis

added) After a prompt by Summers she agreed that it was definitely

Hoover. It is clear that Rosenstiel's story is less than convincing

especially when her claims are considered; Hoover was allowing himself

to be observed by someone who could have destroyed his career and

compromised him for the rest of his life.

Hoover was adept at blackmail. He used

incriminating information his agency collected about prominent people to

maintain his hold on office. The question must be asked: Would a man

with so many enemies put himself in a position to be blackmailed by

parading himself around a hotel dressed as a woman? Furthermore,

Hoover's life revolved around the bureau – would he put his career at

risk by such actions?

Despite the clear implication in the book

that Rosenstiel's story was true, Summers eventually stated that he

merely reported what Rosenstiel said, along with what others claimed. He

said he held, "no firm view one way or the other" as to whether she told

the truth.

Oliver "Buck" Revell, a former associate

director of the FBI, has observed that if the Mafia had had anything on

Hoover, it would have been picked up in wiretaps mounted against

organized crime after Appalachin. There was never a hint of such a

claim, Revell said. Furthermore, Hoover was himself under secret

surveillance for his own protection and such behavior would have been

reported.

The flimsy "evidence" against Hoover's

sexuality was described by former FBI Intelligence Division Assistant

Director W. Raymond Wannall, as, "(emanating from) dead witnesses, a

perjurer, a Watergate burglar, and principally a British author, Anthony

Summers, whose allegations against a previous American public servant,

repeated in a London newspaper, resulted in an open-court retraction,

apology and payment of a substantial sum in damages."

(Author's note: Summers

alleged CIA official David Atlee Phillips had been involved in the

assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The British newspaper The

Observer published excerpts from the book, Phillips sued, and The

Observer admitted in open court that "there was never any evidence"

to support Summers's allegations. The paper apologized to Phillips and

paid £22,500 in damages.)

Wannall questioned why, if "there were

such a photograph with which to blackmail Hoover," was it not used "from

1961 to 1972 when 10 Cosa Nostra "family bosses" were arrested and

convicted, when organized crime convictions based on his investigations

totalled 131 in 1965, 281 in 1968, and escalated to 813 the last year of

his life?"

There are more compelling reasons to

explain Hoover's pre-1961 poor record on dealing with organized crime.

Until 1961, there was no federal law authorizing or enabling the FBI to

investigate organized criminal activities or groups such as the Mafia.

It was not until 1961 that Congress passed a law granting such

authority. It is also true that, after local authorities raided the 1957

meeting of Mafia chieftains from across the U.S. in Appalachia, N.Y.,

Hoover instituted a "Top Hoodlum" program. Several organized crime

figures were arrested long before Congress passed the 1961 law, under

individual laws already in effect. Notwithstanding these facts, it is

true Hoover's war on organized crime did not really take off until the

ascendancy of Robert Kennedy as head of the Justice

Department.

To those who knew both men, including

Cartha "Deke" Deloach, George Allen, and Charles Spencer, Hoover's

relationship with his friend was chaste. Allen said, "Tolson was sort of

Hoover's alter ego. He almost ran the FBI. He's not only a brain, but

the most unselfish man that ever lived. He let Hoover take all the bows

all the credits...They were very, very close because he needed Clyde so

much. He couldn't have done the things he did without Clyde." Spencer

said, "Oh, Christ I heard rumors about them a thousand times. All

around, every place, and I think it's just the result of people unable

to believe that two men could be as dedicated to their country as those

two were. It wasn't just speculation and it was worse than rumors. It

had to be developed by jealous and enviable people that were out to do

somebody in. Their demeanor was always flawless. Very businesslike. The

best way I can put it is that Clyde Tolson was the associate director of

the FBI. He lived 24 hours of every day, seven days a week for the full

year as associate director of the FBI. It was a director and associate

director relationship."

Cartha Deloach worked closely with Hoover

for over 20 years and became the third ranking FBI agent. Deloach

dismissed stories about Hoover's alleged homosexuality stating, "I think

it's significant to note that no one who knew Hoover and Tolson well in

the FBI has ever even hinted at such a charge. You can't work side by

side with two men for the better part of 20 years and fail to recognize

signs of such affections."

The real reason why Hoover did not

investigate the Mafia throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s is that he

had a genuine fear that his agents would be corrupted by the criminal

organization. The FBI was the only love of Hoover's life and he

protected and defended it as a father does with a son. On more than one

occasion he made reference to the fact that state and local law officers

had been corrupted by the mob.

There was also a self-serving reason.

Throughout his leadership of the FBI, Hoover had been unwilling to

tackle any major initiative unless he had been assured of success.

Fighting organized crime, to Hoover, did not provide that guaranteed

success. As Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. wrote, "Former FBI agents laid

great stress on Hoover's infatuation with statistics. He liked to regale

Congress with box scores of crimes committed, subjects apprehended, and

crimes solved. Organized crime did not lend itself to statistical

display. It required a heavy investment of agents in long tedious

investigations that might or might not produce convictions at the end.

The statistical preoccupation steered Hoover toward the easy cases: bank

robbers, car thieves, kidnappers and other one-shot

offenses."

Most importantly, it was Hoover's

obsession with "Communist subversion" that drew his complete attention

and he was aided and abetted in this by successive post-war

administrations and Congresses. He believed communism to be the main

threat to the "American way of life." According to Richard Hack, "It

didn't matter if there were Mafia out there. They weren't going to bring

the government down, they were just making money illegally and there

were lots of cops to deal with that."

It was this desire to keep the fight

against communism at the top of the political agenda that led to his

clash with the first attorney general who saw the Mafia as public enemy

No. 1.

Hoover and the Kennedys

The Kennedys were the most compelling of

J. Edgar Hoover's targets. For over 30 years he dug into the lives of

the Kennedys for political leverage. Beginning with Joseph Kennedy Sr.,

Hoover knew that information about the family would eventually come in

useful. As ambassador to Great Britain during the Second World War,

Kennedy had an important position in President Roosevelt's

Administration and when the ambassador fell out with Roosevelt, the

President turned to Hoover to provide him with details of Kennedy's

promiscuous private life.

However, Kennedy maintained his

friendship with the FBI director and jumped at any opportunity to praise

Hoover publicly. FBI files also record that Joe Kennedy acted as an FBI

informant providing the FBI with names to investigate.

Hoover compiled a file on Joseph

Kennedy's second son, the future president, from the moment the young

naval intelligence officer engaged in a relationship with a married

woman, Inga Arvad, whom the bureau suspected of being a Nazi spy (a

number of FBI memos confirm that there was no truth to the allegations).

The FBI bugged one of the hotel rooms where JFK and Arvad met, but no

proof was found that either he or Arvad had been engaged in spying

activities. However, the fact that Ambassador Kennedy's son had been

conducting a scandalous relationship with a married woman was more than

enough information for Hoover to savor.

Over the years JFK's career moved from

the House of Representatives to the Senate then the presidency in 1960.

By that year Hoover had become the symbol of law and order in the United

States. Hoover's file on the young president grew, delineating numerous

liaisons with women. The file also recorded campaign contributions from

Mafia bosses.

Hoover ordered the accounting of files in

the spring and summer of 1960 when it seemed likely Kennedy would be the

Democratic nominee for president. On July 13, 1960, FBI official Milton

Jones prepared a nine-page memo for Assistant Director Cartha DeLoach,

"...The Bureau and the Director have enjoyed friendly relations with

Sen. Kennedy and his family for a number of years...Allegations of

immoral activities on Sen. Kennedy's part have been reported to the FBI

over the years…they include…data reflecting that Kennedy carried on an

illicit relationship with another man's wife (Inga Arvad) during World

War Two; that (probably January 1960) Kennedy was ‘compromised' with a

woman in Las Vegas; and that Kennedy and Frank Sinatra have in the

recent past been involved in parties in Palm Springs, Las Vegas and New

York City."

After Kennedy was elected president,

Hoover realized that a good way of keeping check on his amorous

activities was to cover Peter Lawford's activities. Throughout the

period of Kennedy's presidency, FBI agents had been ordered to keep

surveillance on Lawford's comings and goings and to make a written

record of any affairs the President had.

On taking office, President Kennedy knew

that the FBI Director had become a national institution, a man who held

a great deal of information about millions of citizens, including

himself. It would take a brave president to get rid of him. On more than

one occasion Kennedy responded to queries about why he did not get rid

of the aging bureaucrat by answering, "You don't fire God." One of the

first acts of his new administration was to reappoint Hoover.

Throughout the Kennedy presidency Robert

Kennedy, the new attorney general, was constantly reminded of Hoover's

secret files. Hoover made a point of sending RFK memos containing

scurrilous information about family members or colleagues as a way of

telling the Kennedy brothers that the director should be treated with

respect.

Hoover hated the Kennedys, believing them

to be moral degenerates. The situation did not improve when RFK became

Hoover's new boss. However, there was never any direct confrontation

between the new attorney general and the crusty FBI director. And as

Hoover was protective and respectful of the Office of the Presidency he

was at all times civil and obedient to President Kennedy. Although he

was irked at orders from RFK, he never challenged the attorney general.

Hoover's bureaucratic instincts told him that it would be futile to

challenge the President's brother and closest confidante.

In the past Hoover's relationships with

attorneys general had been founded upon their unwillingness to challenge

the FBI Director's semi-autonomous position within the Justice

Department. Attorneys general had allowed Hoover to govern the FBI

without interference and to report directly to the president. The

situation changed after the appointment of Robert Kennedy; Hoover was

forced to deal directly with the President only through the office of

the attorney general. RFK placed a direct telephone link on Hoover's

desk and made it plain that the director was his subordinate. When

Robert Kennedy took office at the age of 35, Hoover was 65 years old and

knew he did not have to retire until Jan. 1, 1965 when he would have

reached the age of 70. Hoover therefore did not want to directly

challenge RFK and risk a premature end to his career.

Nevertheless, the relationship was

adversarial. On one occasion Hoover said to an aide, "They call him

‘Bobby'!" It was evident to those close to the FBI Director that Hoover

would not enjoy working with a young activist like Kennedy. Hoover was

the quintessential bureaucrat who lived by rules. The young attorney

general frequently broke the rules by appearing at meetings in

shirtsleeves. He generally encouraged a relaxed and informal atmosphere

within the Justice Department. Hoover, on the other hand, frequently

remonstrated with subordinates who did not adhere to the appropriate

dress code. And, if an agent was found to have had extra-marital

relations, he was immediately transferred to a less prestigious

posting.

FBI Agent Courtney Evans, who was

appointed by the Kennedys to be the FBI liaison with the White House,

felt that Hoover and RFK were too much alike to be effective colleagues.

"When I looked at Bob operating in 1961," Evans said, "I figured that's

the way Hoover had operated in 1924...the same kind of temperament,

impatient with inefficiency, demanding as to detail, a system of logical

reasoning for a position, and pretty much of a hard

taskmaster."

There was probably an element of jealousy

in Hoover's relationship with RFK. Hoover believed that nationally

organized crime did not exist and felt there was no evidence that it

did. When Robert Kennedy became attorney general, those agents who had

been assigned to investigate organized crime were immensely overjoyed.

They knew Robert Kennedy was a committed crime fighter who would throw

all the resources of the Justice Department behind fighting the Mafia.

Because of his previous work as a counsel to Senate investigating

committees, Kennedy understood, as few officials did in the 1950s, the

true nature of the mob. It was not a loosely knit band of non-violent

criminals who served the public's harmless appetite for gambling but

instead a powerful and insidious organization in U.S. society. In fact

Kennedy knew that the Mafia, through its control of many labor unions,

greatly affected the welfare of every man woman and child in

America.

The scope and success of RFK's campaign

against organized crime was unprecedented. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

(Robert

Kennedy And His Times, 1978) wrote, "Subversion was out.

Organized crime was in. Hoover grudgingly went along."

There were a number of other reasons why

the relationship with the Kennedys got off to a bad start. Although

Hoover had been friendly with Joseph Kennedy he had little respect for

his sons whom he considered to be upstarts. Hoover knew about John

Kennedy's womanizing and took the view that he was unfit for public

office and that his character was weak. Hoover had been a lifelong

bachelor, mother-dominated, and raised with strict puritanical and

Calvinist strictures. JFK's liaisons, faithfully reported on by Hoover's

agents, obviously upset the FBI director's moral equilibrium.

Hoover's knowledge of John Kennedy's

affair with the Danish beauty, Inga Arvad, had been useful in his

relationship with Joseph Kennedy. However, it was not until the

presidential election of 1960 that Hoover began to take a deep personal

interest in the Senator's private life. He became disgusted with reports

emanating from Las Vegas, a favorite Kennedy stopover in the

presidential campaign. A report in 1960 to Hoover described orgiastic

goings-on during the filming of the Sinatra Rat Pack's movie Ocean's

11. The report stated, in part, "Show girls from all over town were

running in and out of the senator's suite."

Hoover also had a photo of Sen. John

Kennedy leaving the home of his wife's secretary, Pamela Turnure, in the

early hours of the morning. It was the secretary's landlords, the

Katers, who informed the director and the couple began a vigorous

campaign to reveal Sen. Kennedy's adulterous acts. However, the media

largely ignored their campaign. An extreme right-wing magazine called

the Thunderbolt published their story and this gave Hoover the

excuse to bring it to the attention of the Kennedys.

This is an excellent example of how

Hoover operated. Hoover could not use his subtle blackmailing techniques

by referring to his agents' reports. The Kennedys would have been

outraged that the FBI director had been snooping on them. However, if

scandalous material had been disseminated through other organs, Hoover

could righteously say that he was bringing the offending material to

their attention and "protecting" them.

Hoover knew he could act contemptuously

at times. He well understood the respect and admiration that leading

groups in the United States held for him. In fact his popularity

remained at an all-time high. Kennedy's close victory also meant the new

president could not act boldly in changing the status quo. As Robert

Kennedy said, "It was important as far as we were concerned that

(Hoover) remained happy and that he remain in his position because he

was a symbol and the President had won by such a narrow margin and it

was a hell of an investigative body and he got a lot of things done and

it was much better for what we wanted to do in the South, what we wanted

to do in organized crime, if we had him on our side."

Even though Hoover maintained a civil

attitude to the Kennedys during John Kennedy's presidency, he and the

Kennedys worked together in an atmosphere of hatred and

mistrust.

It was the knowledge of one of President

Kennedy's girlfriends that led Hoover to believe he could intimidate and

embarrass the President. FBI reports indicated that Judith Campbell

Exner had frequent contacts with President Kennedy from the end of 1960

to mid-1962. (They actually met earlier when Kennedy was running for

president and were introduced by Frank Sinatra.) The reports said that

Campbell was a close friend of gangster, Johnny Rosselli, and Chicago

mob boss, Sam Giancana, and she saw them often during this period.

Hoover became concerned that the Mafia would use this connection to gain

influence with the President. He also no doubt felt that this was a

golden opportunity to make Kennedy aware that he knew about the affairs

under the guise of keeping track of criminal figures. Hoover sent

identical copies of a memorandum, dated Feb. 27, 1962, to Robert Kennedy

and Kenneth O'Donnell, assistant to President Kennedy. The memo stated

that information developed in connection with an FBI investigation of

Johnny Rosselli revealed that Rosselli had been in contact with

Campbell. Hoover's memo also stated that a review of the telephone calls

from Campbell's residence revealed calls to the White House.

On March 22, 1962, Hoover had a private

luncheon with President Kennedy. There is no record of what transpired

but, according to White House logs, telephone contact between Campbell

and Kennedy occurred a few hours after the luncheon. Historians are in

agreement that it is likely Hoover used this meeting to apprise the

President of how reckless and dangerous it was to be connected to a

woman who was also friendly with members of the Mafia. Hoover was using

subtle blackmail.

In the two years and 10 months of

Kennedy's presidency, Hoover had only been invited to White House

functions a dozen times. Hoover was also unhappy that he could no longer

contact the President directly as he had done under previous presidents.

His relationship with both RFK and JFK was dangerously cunning to say

the least. Yet there is nothing in the record that Hoover tried to harm

President Kennedy by leaking information even though the FBI director

relished the opportunity to show Kennedy that he knew a lot of

secrets.

Athan Theoharis has described Hoover as

an "astute bureaucrat" who, "recognized that a direct attempt at

blackmail could compromise his tenure as director. So he volunteered

information only after it was already public...or had been obtained

incidentally to a wiretap installed during an authorized criminal

investigation (such as the information involving Kennedy's contacts with

Judith Campbell, obtained through a wiretap on organized crime leader

Johnny Rosselli). A sophisticated blackmailer, Hoover only hinted at the

FBI's ability to monitor personal misconduct."

In effect, there was a stand-off between

the President and the FBI director. Hoover's secret files contained

information that could have done irreparable damage to the Kennedy

administration: JFK's womanising, CIA/Mafia attempts to kill Castro, JFK

friend Frank Sinatra's links to mob bosses, and Sinatra's efforts to

enlist the Mafia to help in the 1960 presidential campaign. Kennedy on

the other hand could have fired Hoover at any time during his 1,000-day

presidency. Kennedy could also have embarrassed the director for not

recognizing the importance of organized crime and not responding,

initially, to equal-rights directives within the FBI. Effectively, it

was a "Mexican stand-off."

It would be Robert Kennedy's efforts to

protect his brother from a scandal that solidified Hoover's hold on his

job. During the summer of 1963 RFK asked Hoover to help in persuading

Congressional leaders to desist in linking their investigation of

corrupt practices by Senate Secretary Bobby Baker to members of the JFK

Administration. Baker was accused of influence peddling and during the

investigation of his affairs it was revealed he had been supplying

leading Congressmen with "party girls." One particular woman, West

German Ellen Rometsch, who was taken to the White House by Kennedy

friend Bill Thompson for an intimate meeting with JFK, was in a position

to bring down the Kennedy presidency. Robert Kennedy enlisted the

assistance of Hoover who spoke to Congressional leaders about the damage

the Baker revelations would do to both Democrats and Republicans. The

investigation continued but without reference to the Quorum Club which

was the center of Baker's enterprise.

Hoover was now assured he had enough

information to hold the upper hand in his dealings with the Kennedys and

this may account for RFK's acquiescence in Hoover's request to tap the

telephones of Martin Luther King Jr. It now became impossible for JFK to

get rid of Hoover. He would have to wait until his re-election in 1964

and Hoover's statutory retirement in January 1965 before he could rid

himself of a dangerous subordinate. However, JFK's assassination and the

elevation of Hoover's friend Lyndon Johnson to the presidency, put an

end to the threat hanging over Hoover's head.

Hoover's Legacy

Hoover ran the Bureau for nearly 48 years

prior to his death on May 2, 1972. When he became director in 1924, it

was called the Bureau of Investigation and was inefficient and

scandal-ridden. But, according to most Hoover biographers, the new

director quickly turned it into an efficient and uncorrupt policing

agency. Hoover abolished political appointments, recruited highly

educated agents, instituted centralized fingerprint and statistical

files, developed a crime laboratory and founded a highly acclaimed

training academy. As investigative reporter and Hoover nemesis Jack

Anderson wrote, "J. Edgar Hoover transformed the FBI from a

collection of hacks, misfits and courthouse hangers-on into one of the

world's most effective and formidable law enforcement

organizations. Under his reign, not a single FBI man ever tried to

fix a case, defraud the taxpayers or sell out his country."

Those who knew Hoover throughout his life

are divided in their judgments of the man. To some, Hoover was a

patriotic and dedicated public servant who believed in American

democracy and built the finest crime-fighting agency in the world. He

was neither arrogant nor a megalomaniac. Former agents of the bureau

speak of Hoover as a man who instilled in them the highest qualities of

service and pride in the agency's work.

Hoover defenders also explain why he

remained a bachelor. According to Richard Hack, "For J. Edgar Hoover to

be as powerful as he was, to maintain that image, he gave up his

personal life. It became his personal life. There was no other

life."

Hoover's admirers characterize him as a

friendly man of great humor who enjoyed being with people. Actor James

Stewart is typical of a group of acquaintances who described Hoover in

this way. Stewart characterized Hoover as a man who, "...liked to be

with people, and I thought always that he was very easy to be with and

it always surprised me...he was so easy to be with and so easy to talk

to…I had the feeling that I was with a very strong, determined man,

always."

Hoover's detractors, on the other hand,

have described the director as a man trapped in his past – a past that

glorified in a WASP America. Hoover's American ideal was not in keeping

with any progressive cause or a toleration of foreigners, radicalism,

and left-wing politics.

Detractors characterize Hoover as a man

who had a lot of prejudices, disliking Jews, African-Americans and

"pseudo-liberals"; as a man who saw enemies of the state everywhere and

it was his God-given right to protect the nation. To these critics

Hoover was, essentially, the major threat to American liberties. They

describe him as a man who spent too long in the job, becoming

increasingly senile, angry and personally corrupt, misappropriating

government time, money, services and equipment for his own ends and for

having accepted gratuities from Dallas millionaires Clint Murchison and

Sid Richardson.

Critics of Hoover point to the extensive

use of illegal investigative techniques including "black bag jobs,"

illegal break-ins) wiretaps, bugs and illegal mail-openings. Although

Hoover often ordered his agents to commit aggressive and sometimes

illegal acts against individuals and organizations engaged in legitimate

political activities, it was clear to many that some of Hoover's

practices must have been, if not condoned, at least allowed by every

president he served under. The presidents Hoover served under cannot

escape blame.

As a law enforcement agency, the bureau

had all the resources needed to eavesdrop and wire tap citizens

suspected of breaking federal laws. But those same resources were also

used to uncover evidence of immoral behavior by senators and congressmen

and were savored by the presidents he served. Although Eisenhower

disdained Hoover's methods he made no attempt to curb the awesome power

the bureaucrat had accumulated. Nor did Nixon. Roosevelt and Johnson

especially appreciated the information Hoover channeled their way,

gleefully reading scandal–filled reports of their political enemies'

private lives. During his years in the White House President Johnson

included in his private conversations references to the private lives of

congressmen that could only have come from surveillance.

Hoover did not see himself as personally

corrupt, even though he had passed on many of his personal expenses to

the bureau. When Hoover's expenses could not be stretched he accepted

"hospitality" from businessmen. However, if one of his agents abused his

expense accounts he would be severely disciplined. Hoover would also

vacation with Clyde Tolson at the expense of the bureau and then arrange

to have a brothel or illegal saloon raided so he could claim he was

"working." There is also evidence that Hoover was guilty of tax evasion.

Hoover had been head of the FBI for

decades and considered himself above reproach in giving himself some

leeway in accepting relatively small gratuities. There is no evidence,

however, that he enriched himself to the tune of millions of dollars

through his position as head of the FBI. The fact that he and Tolson

took annual "inspection" trips to the Miami area and Southern California

and had his agents do work on his home and car were the most serious of

his ethical lapses. The fact his estate was fairly modest was testimony

to the fact that he had not been bought off in any significant way. And,

in later years, he worried that he would not be financially secure in

his old age and accepted what was common and legal up to the 1970s

--honorariums accompanied by large checks.

Allegations of Hoover's greed can also be

tempered by his refusal to accept higher paying jobs that were always on

offer from large corporations. At one point in his career Hoover had

been offered a lifetime job by billionaire Howard Hughes but turned it

down. Hughes told Hoover that he could set his own salary. Instead,

Hoover wished to remain with his true love: the directorship of an

institution that he had personally built.

Hoover was not a Soviet-style secret

policeman. Nor was the FBI a kind of Gestapo. But Hoover and the bureau

did evade public scrutiny, invade the private lives of Americans, and

resisted democratic control. Under Hoover's COINTELPRO program the FBI

"neutralized" the American Communist Party by infiltrating agents and

destroying the reputations of many of its leaders. It infiltrated New

Left student groups and made every effort to disrupt the activities of

its members. As the civil-rights movement grew, the FBI pinpointed every

group and potential leader for intensive investigation. The FBI wrongly

accused the NAACP of harboring Communist-controlled agents within its

leadership. The Congress of Racial Equality, the Student Non-violent

Co-ordinating Committee, and the Black Panther Party were listed by the

FBI as "Black-Hate" type organizations and selected for covert

disruption of their political activities. One of the most vicious FBI

attacks was made against Martin Luther King Jr. with Hoover personally

conducting the efforts to destroy the civil rights leader's reputation.

Hoover's defenders, however, claim that

this period in American history, when riots and dissent appeared to

usher in anarchy and revolution, called for extra-legal measures to deal

with the problem. While not excusing Hoover's lack of proportion in

dealing with the problems, they remind critics that a great fear existed

in the country that society had been threatened with a breakdown in law

and order. They also remind critics that Hoover came under considerable

pressure in the 1960s by U.S. presidents who were anxious to deal with

anti-war riots and civil-rights disturbances, believing that every time

a riot or disturbance occurred it lost them votes. Hoover believed his

vendetta against political dissent, his reaching beyond the law to

prevent lawlessness and anarchy was within the mandate set down by

higher authorities.

J. Edgar Hoover was a complex and

contradictory individual. He set high standards for his agents yet was

himself less than circumspect when it came to using taxpayers' money for

his own ends and he was capricious in his dealings with

agents.

Hoover was a decisive man, strict and

authoritarian – precisely what the bureau needed in the 20s and 30s. But

as he grew older, he did not adapt to changing times. His autocratic

style became increasingly challenged by the new demands of a 1960s

liberal America. As historian Michael O'Brien opined, "(Hoover was) …an

aloof, smug, narrow-minded, martinet with an imperial ego…."

When his body lay in the Capitol,

politicians came forward to extol Hoover's patriotism, his defense of

the "American Way" and his single-minded obsession in making the FBI the

No. 1 crime-fighting agency in the world. But they were also secretly

relieved to see his passing. And, three years after his death, the U.S.

public was so outraged that such vast reservoirs of power could be

wielded by an unelected "civil servant" that Congress became determined

never to allow it to happen again, passing a statute that restricts the

FBI director's tenure to 10 years. Hero or villain, America will never

see another J. Edgar Hoover.

Mel Ayton is the author of The

JFK Assassination: Dispelling The Myths (Woodfield Publishing

2002) and Questions

Of Controversy: The Kennedy Brothers (University of Sunderland

Press 2001).

His latest book, A

Racial Crime – James Earl Ray And The Murder Of Dr Martin Luther King

Jr., was published in the United States by ArcheBooks in

February 2005.

His latest book, A

Racial Crime – James Earl Ray And The Murder Of Dr Martin Luther King

Jr., was published in the United States by ArcheBooks in

February 2005.

In 2003 he acted as the historical adviser for the

BBC's television documentary "The Kennedy Dynasty" broadcast in November

of that year. He has written articles for Ireland's leading history

magazine History Ireland, David Horowitz's Frontpage

magazine and History News Network.